Cashing out of an employer-sponsored retirement plan is possibly the single most harmful decision to achieving a financially secure retirement that an employee can make — next to not contributing at all.

Any withdrawal of funds from a defined contribution plan is subject to prevailing local, state and federal taxes and a 10% early distribution penalty. Most significantly, the amount cashed out loses the potential for investment growth — a loss American employees can ill afford.

According to data released in 2017 by the American Benefits Council, the number of Americans participating in their employer-sponsored defined contribution plan is 94.6 million. EBRI research estimates 14.8 million (22%) of active and contributed defined-contribution participants will change jobs each year. Of these job changers, Retirement Clearinghouse reports some 41% will cash out their retirement plan.

As these statistics reveal, employees are cashing out of their employer-sponsored defined contribution plans at an alarming rate — with detrimental consequences for their future retirement security.

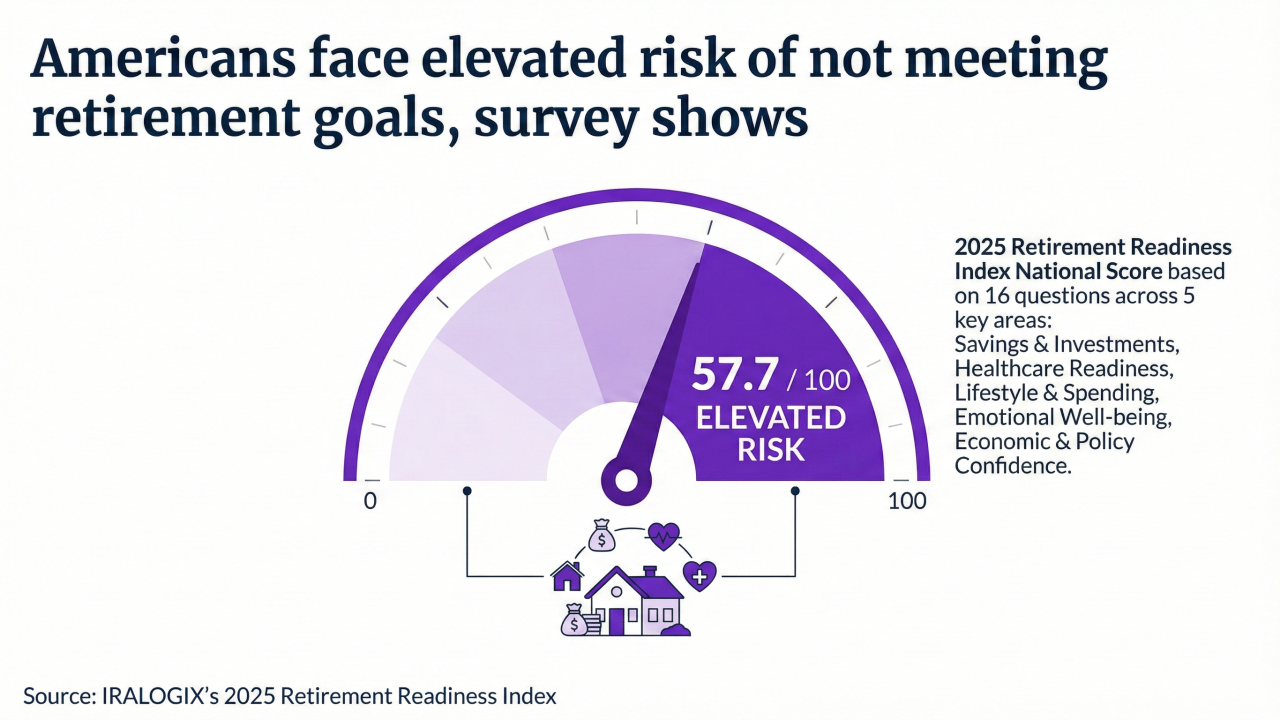

Nearly half of Americans approaching age 65 have less than $25,000 saved, according to EBRI; one in four have less than $1,000 saved. According to

How grim is the outlook for inadequate preparation for retirement? Consider this prediction from a

As illustration of the harmful impact a cash out has on future savings, consider this example. A 35 year old withdrawing $15,000 from an employer-sponsored defined contribution plan, assuming a federal tax rate of 22% and a state tax rate of 5% (total of $4,050) and including the 10% withdrawal penalty ($1,500), ends up with $9,450. Assuming a conservative interest rate of 4%, that $15,000, if left in the retirement account until age 65 would’ve grown 224.68% to $49,702.

Employees who have either lost their jobs or are changing employers need to understand that they have options other than cashing out. The first of these is to roll their retirement plan assets into the new employer’s plan.

This is, hands down, the best option, as having all an employee’s retirement funds in one place makes it easier to track and manage them. To help employees through the consolidation process — which can be clunky at best — most plan record keepers have assembled teams to help participants go through the process to completion.

The second option is to leave the retirement plan assets in the current employer’s plan. This is particularly attractive for employees with certain types of assets in their current plan that are not available in the new employer’s plan, such as company stock. This is also a good idea for those moving from a large employer to a small employer, as large employer plans typically have lower fees and more service offerings. That said, leaving assets in a former employer’s plan should never be viewed as a signal not to continue contributing or not to contribute to the new employer’s plan.

The third option is to roll retirement plan assets into an individual retirement account. For most employees, this is the option of last resort. Individual retirement plans are typically more costly than employer plans. Employer plans are usually able to offer lower costs, which are achieved with the buying power and clout of their size. That said, sophisticated individual investors may choose an IRA to have the ability to participate in tax-deferred investments not offered by employer plans, which tend to be more conservative.