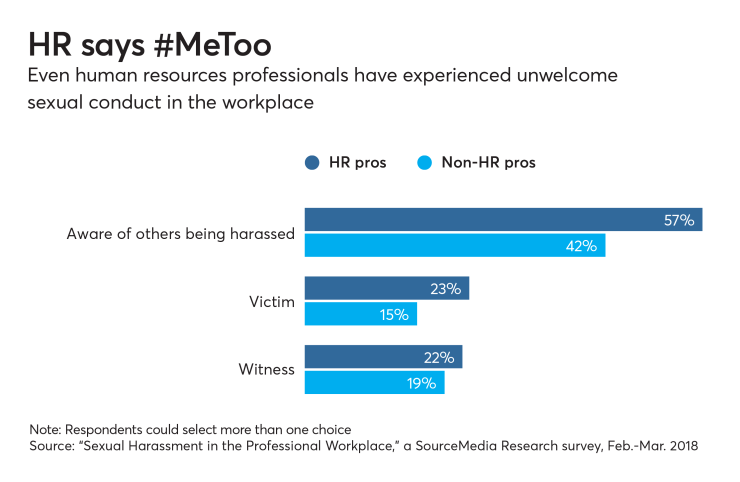

The #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, where women and some men are calling out sexual harassers and abusers, have sent shockwaves through every industry — from Hollywood to banking, farming and restaurants — and human resources departments are increasingly inquiring about digital tools to aid in the education, tracking and prevention of these incidents.

“Employees feel that reporting harassment comes at a significant cost to their career,” says David Walton, a Philadelphia-based labor and employment attorney at law firm Cozen O’Connor. “If we can provide a safe way for employees to report, we can help more people. An app may make it easier.”

Tech-enabled tools, such as AllVoices, Bravely and Callisto, launched within the past three years and have garnered a lot of media attention — but not necessarily high utilization rates, as these tools are not quite yet omnipresent in the workplace.

AllVoices, an app announced to much fanfare in November 2017, allows employees to anonymously report incidents witnessed or experienced firsthand directly to their CEO and company board, circumventing human resources altogether. The app is still in beta testing and has not yet launched. Multiple emails and calls to AllVoices CEO Claire Schmidt and her team went unanswered, and no companies have publicly signed on to using AllVoices.

Meanwhile, there’s Bravely, an HR telemedicine-type platform launched in June 2017, which connects employees with third-party HR professionals to discuss any type of workplace conflict, from sexual harassment to preparing for a difficult annual review. Coaches help employees create strategies for dealing with those situations.

The platform, which is offered to employees through an employer at $5 to $8 per employee per month, aims to foster better communication in the workplace, says Toby Hervey, cofounder and CEO of Bravely.

In most cases of workplace harassment, experts say, offenders aren’t aware their comments constitute harassment under state laws and company policies, and a conversation with the offender can often solve the problem.

For extreme cases though, like that of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, Bravely allows employees to file an anonymous complaint after an online session with a third-party HR professional, which is then escalated to the company’s human resources team; Bravely also generates reports to highlight issues and trends of conflict at a client’s office, Hervey says.

Hervey declined to share how many companies use Bravely but has said those clients are mostly technology companies and fast-growing startups.

A majority of employees using Bravely are women, people of color or LGBTQ-identifying, according to the company.

“They're coming to us to tackle issues that are related to their identities, or facing a greater intimidation or fear factor around routine performance issues given they’re sometimes lacking representation in their workplaces,” Hervey says.

About one in four complaints (27%) received by Bravely are on workplace relationship challenges, according to the company. Bravely says it is unable to specify the percentage of complaints concerning protected classes or harassment, but notes less than 1% of sessions contain allegations of harassment.

Callisto is another reporting tool that is mostly used at a dozen colleges and universities, including Stanford University. The tool’s pilot program launched at the University of San Francisco and Pomona College in August 2015; Callisto later gained prominence when it was deployed at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, an improv training center, in April 2017 after a comedian was banned amid rape and sexual harassment accusations.

The platform, which allows students to report sexual assault and send a copy of the report to their institution for further investigation, also creates a database to identify repeat offenders. Institutions are notified if two or more reports are filed against one individual. Callisto charges institutions a flat annual rate based off the student body size, according to the company.

If Callisto is available at their school, sexual assault survivors are five times more likely to report their assault than survivors who did not, according to the company. On average, survivors using Callisto will take four months to report their assault, compared to the national average of 11 months, according to the company.

Callisto is also working on a pilot program slated for this year that will expand its system to detect repeat perpetrators across professional industries. Like the campus tool, users can identify their perpetrator; if another person within the organization reports the same perpetrator, a Callisto counselor will reach out to guide those employees through the reporting process and their choices, and offer to connect them with those who were assaulted by the same perpetrator.

“In the wake of #MeToo, we've certainly received many inquiries about our reporting platform — specifically regarding how it might be adopted outside of the campus setting,” the company said in a statement. “There's definitely a hunger for scalable ways to address this long-standing, pervasive social issue.”

The number of apps and platforms to encourage and streamline reporting is an obvious progression from more traditional reporting methods, such as forms and call centers, yet lawyers, HR experts and tech companies themselves don’t see reporting apps as the sole solution to rampant workplace harassment.

“If we think tech is going to fix everything, we’re missing the point here,” Hervey says. “This is a cultural thing. Training is an important part of this, changing norms, equal pay and key policies” like equal parental leave and representation at the top, he added.

Policies and procedures, company culture and reporting systems dictate how employees should interact and report harassment.

Training is an important part of the equation, experts say, although attorneys and consultants emphasize that the most efficient training is done in person, not using apps or platforms.

Also in this series:

Don Phin, a former attorney who litigated sexual harassment cases for more than a decade but currently works as a trainer and executive coach in San Diego, says he sees more employers stepping up training and educating employees on company policies and procedures in light of the #MeToo movement. However, there haven’t been dramatic changes to reporting since Anita Hill’s testimony against Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, he says.

“All this tech does is streamline the system, allows it to be case managed,” Phin says. “Two-thirds of women in their career have suffered sexual harassment. Is somebody teaching women how to deal with this? What do you say to somebody who says something wrong to you?”

Likewise, the training around workplace harassment is more focused on situations that constitute harassment but not necessarily avenues for reporting. If reporting technology does exist in the workplace, improper utilization or implementation can undermine the system entirely.

“Anything you can do to help the employees feel there’s a place they can go to be heard, the better,” says Dave Berndt, senior client advocate with G&A Partners, a Houston-based professional employer organization. “But if people feel like, ‘What’s the use of calling this new channel for reporting and nothing’s going to happen,’ you just invalidated that whole solution.”

Berndt says it’s crucial for companies to have an open-door policy, where employees can speak to anyone, from the C-suite to HR and their manager, about any harassment they may be facing without feeling they could be retaliated against or not taken seriously.

“Until people feel that, people will not want to come forward and talk,” he says.

Some companies, such as Catholic Charities New Hampshire, outsource the reporting method and use a call center to create a safe space for employees to report sexual harassment.

David Twitchell, vice president of human resources at Catholic Charities New Hampshire, says the #MeToo movement prompted a discussion within the C-suite (which he is a part of) and the board to review the company’s harassment policy and look at how they could help employees and customers report cases of abuse. Catholic Charities New Hampshire has 1,020 employees and runs seven nursing homes, manages an additional home, and has several social service functions and offices across the state. It needed a hotline that could identify harassment or assault occurring internally or at one of its properties.

So the organization brought on NAVEX Global, a SaaS-based reporting system recommended by a Society for Human Resource Management member, for less than $5,000 in the first year. The annual fee drops down to less than $3,000 every year after, Twitchell says.

“We’re also well aware of the fact that there are a lot of employees who are fearful to raise an issue like [sexual harassment],” he says. “We can at least provide some kind of mechanism where they felt comfortable.”

Employees can call in through a 1-800 number or use their computer to file an anonymous complaint, which will trigger an internal investigation and provide data points for Catholic Charities New Hampshire to determine if there’s a pattern.

Across NAVEX Global’s clients, cases took about 44 days to close in 2017, up from a median of 42 days in 2016, according to the company’s annual benchmark report. NAVEX Global doesn’t maintain aggregated data on the types of complaints they’ve received, such as verbal harassment or physical abuse regarding sexual or gender issues.

If we think tech is going to fix everything, we’re missing the point here.

The report says that case closure time can influence whether an employee feels their issue is being taken seriously.

“With a median of 44 days, this means that half the cases in the database are taking longer than 44 days to close,” according to the report. “This could be an indicator of insufficient resources and potentially increased legal oversight of matters raised.”

NAVEX Global has a “very refined intake process” to ask the reporting person questions that ensure the reports are made in good faith and are useful to the human resources department receiving it, says Carrie Penman, chief compliance officer and senior vice president of advisory services.

“The specialists are trained to take each report professionally and respectfully, and their focus is on accuracy and clarity of the information to ensure that the customer receives actionable information to conduct a full investigation of the report,” according to the company.

Unlike internal reporting measures, Penman says NAVEX Global hosts the data for its 13,000 global clients and creates enough distance from the HR department to make an employee feel comfortable with reporting unwanted behavior.

Phin is skeptical, in general, about the use of these technologies and apps.

“Is technology going to embolden [an employee]?” he asks. “Is that safer than talking to someone in HR? Then why the hell is that?”

“What’s wrong with HR?”